You read that right: 85%. My family of four uses, on average, 4.7 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity per day. Our electric bill never tops $32 per month. In the past we used just over 30 kWh/day, which is about average in the U.S., although there is huge variation. In our state, the average is over 36 kWh/day.

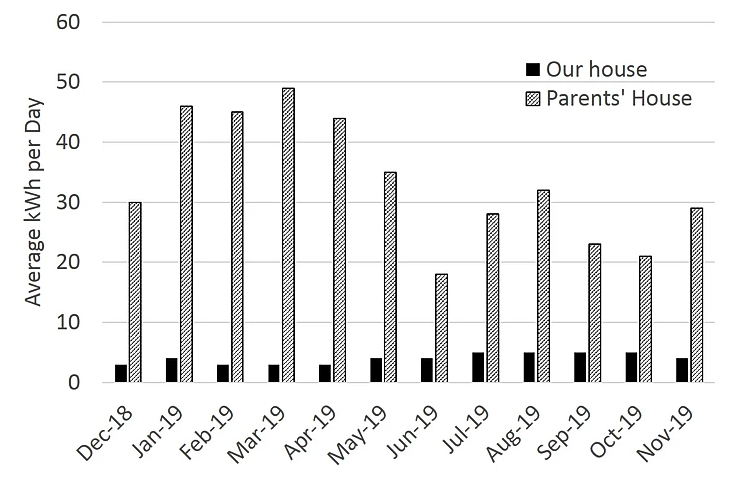

Let me hit you with a graph right away. The gray bars represent my parents' usage, which is real similar to how ours was before we started cutting, and similar to the average American usage. We had an unusually hot May and cool June this year, so air conditioning for those months was inverted. Thanks to my husband the Data Fiend for the beautiful graph.

Of the electricity generated in America, 38% is used in homes. Another 37% is used in commercial settings, and the rest in manufacturing. Individuals obviously have much less influence over these last two categories, but it certainly can’t hurt to shop less, buy less, buy used and retire early. At the very least, that’s all good for the bank account and the clutter level.

Back to homes, since that’s where we have the most control. What’s the problem with all that juice, anyway? First of all, it amounts to over 9.5 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent into the air per household per year, using U.S. average grid emissions of 1.45 lbs/kWh carbon equivalent. (Check out this awesome tool to see how your zip code compares in its mix of electricity generation, and discover the carbon footprint of your actual kilowatts. Note that the tables are in megawatts not kilowatts, and the carbon chart is just carbon, with the other greenhouse gasses separated out.) But the impacts of electricity generation don’t stop there. There’s also the environmental toll of mining coal, the water impacts of fracking for natural gas, and the thorny issue of storing radioactive waste from nuclear reactors.

Luckily, renewables such as wind and solar have been growing quickly. Now, don’t get me wrong. I think electricity is an indispensable tool and renewables are definitely a move in the right direction. I hope we keep building them out and learning to use them better. But even with all the recent growth in renewables, global fossil fuel use is also still growing, because demand is still growing. All our building of renewables hasn’t reduced our use of fossil fuels at all, and it never will as long as people continue to demand more power. People in developing countries need that power, so kids can do their homework and hospitals can function. Americans are not getting increased benefits from increased electricity usage.

There is also trouble on the horizon with the eventual disposal and subsequent remanufacture of wind turbines and solar panels. There are issues involving transmission equipment and intermittency that are not always accounted for. Even if it were possible to mine the materials and build the components for renewable energy without fossil fuels (which it currently isn’t), we can’t scale them fast enough to avert climate disaster while maintaining our current level of electricity consumption. We simply must. Use. Less.

Using less buys us time to transition to cleaner fuels, because it lowers the amount of pollution we put into the atmosphere right now, instead of waiting five years or fifteen. Using less might make it possible to run our society on renewables, and give electricity access to people who haven’t had it without frying the globe. Using less saves money today.

So how did my family become super-low electricity consumers? It wasn’t arduous and it wasn’t immediate, but more like a gentle meandering journey toward new ways of getting things done. Not every suggestion here is applicable to every household because we all have different time and money constraints. You have to do what works for you and then share it with us in case it might work for us, too. I recently had a houseguest who called my house “primitive,” and he’s not wrong. It’s very different from the average American house, and from the house I grew up in. However, in this case, primitive does not mean uncomfortable, dirty, or even particularly inconvenient. Just much less environmentally damaging.

Our journey started when our roommate moved out and took his clothes washer and dryer with him. I was seven months pregnant with my first child. I did not want to spend a huge chunk of change on white goods. I did not want to drive the production of more appliances, or pay to run a dryer, or heat up the house and the planet while wearing out my clothes faster.

We bought an Energy Star front-loading washer, but not the matching dryer. Even though we live in a very humid area. Even though I was planning on cloth diapering (eventually I cloth diapered two at once without a dryer). It’s not perfect. About twice a year when it rains for weeks or the cat pees on something, I take an almost-but-not-quite-dry load to the laundromat on my way somewhere else and give it 75 cents’ worth of time in their dryer.

The rest of the time I hang our clothes on my handmade rack. Washer and dryer together use about 13% of household electricity, but the dryer uses over 9/10ths of that, so with one little change we reduced our impact by at least 10%. (Check out this graphic to learn about energy usage in your house.)

I like hanging clothes. It doesn’t take long. It’s a nice moment to quietly think, write something in my head, plan the garden or answer questions from small children. The clothes usually smell better, and they last much longer. I never get behind on the laundry because I don’t suffer from the illusion that I can do eight loads in a day if it piles up, which means, check it out: I never have to spend a whole day doing laundry! How cool is that! I just do a load whenever it’s nice enough, and it nearly always works out fine. If you think you can’t possibly swing it, you could still give it a try and find out for sure. A clothesline is cheap, and you don’t even have to get rid of the dryer, just pause for long enough to get the knack of hanging. I know somebody who hangs dries even though she has ten children.

It’s the same deal all over our house. We choose to give a few extra minutes of our time or a little bit more thought and management in exchange for huge reductions in electricity usage. Flip that around: Americans use huge amounts of electricity to shorten daily tasks by a few minutes or make them very slightly more convenient. All those have negative impacts on the planet and our collective future, just to gain a few minutes, a smidge more convenience. If I chose that, I could think of no reasonable way to explain it to my children, who will have to live in that degraded future we all make by our choices today.

After we got rid of the dryer, we replaced the inefficient light bulbs. In a typical house these might be using 12% of power, while equivalent LEDs use 1/10th as much or less. Then we corralled the energy vampires, which waste up to 13% of total usage. The big computer screen we use for a TV is on a switch. It can be turned all the way off during the 22 hours a day it’s not in use, instead of continuing to draw power. We have just one of these because we’ve gotten rid of most of the machines that don’t truly serve us, but many houses have dozens of devices in this category. And if you have a leaky house, it’s worth another 10% to seal up cracks and add some insulation if you can afford to, especially in the ceiling. It’ll pay you back over time.

So, let’s add that all up. In a house that uses the average 30 kWh/day, these easy changes that don’t cost much in time, money or convenience could potentially save: 3 kWh/day on lighting, 3.9 on standby energy vampires, 3 on heating and cooling by reducing leakage, and 3 on the dryer. Converting those kWh/day to carbon and pocketbook savings, that’s 3.5 fewer tons of carbon put into the air every year and a 43% reduction in the electric bill.

Close to half the electricity usage in an average house is heating and cooling, and after the cracks are sealed it’s not quite as easy to make more change there. Most of us are stuck with the houses we have and the systems already in place, but there is wiggle room. Lots of folks zone heat, warming just the rooms they’re currently in or just the ones that are used most often. Personal experience with my wood stove has taught me that a house that is different temperatures in different rooms and at different times of the day is much more comfortable than one that is 67 degrees everywhere always. Many people turn down their thermostats at night and in the winter. I know a family who does just fine heating to 65 degrees during the day and 55 at night.

When I lived in forced-air houses, I used to shut off the thermostat for several months in the spring and fall. Open the windows in the morning and close by midday to cool the house down when the weather is trending too warm. Open them at noon and close at dinner to heat the house up when the weather is trending too cold. Of course, this is less workable if you’re gone to work all day every day or if your climate has shorter shoulder seasons, but it’s an option for lots of people. It takes just a moment, it smells better than air pumped through ducts, and the house is quieter because the fans that move all that air around don’t have to run; the breeze does that job automatically.

For cooling, ceiling fans are a huge benefit. A fan makes it feel five degrees cooler in the room, and the moving air helps combat humidity and still pockets. Just make sure to turn them off when people leave the room because it only feels cooler, it doesn’t actually make the air cooler. Fans are very cheap to run for the benefit they give.

As someone who moved from the north to the south, I seriously appreciate air conditioning. However, when it’s hot outside each degree the house is further cooled uses more electricity because insulation only slows the transfer of heat through walls, rather than stopping it. The greater the difference between inside and outside, the faster the transfer, and the more energy necessary to achieve each subsequent degree. You can save a lot by just letting the house be a few degrees warmer.

The human body gradually gets used to warmer temperatures if it’s not being continually refrigerated. This helps a person better tolerate the heat when they do venture outside, and it can reduce the risk of serious health problems such as heat stroke. Bumping the heating down and the cooling up to better match the outside temperature (even if you only do it while people are sleeping or out of the house) can save 10%, or another 3 kWh/day.

When we built our little house, we thought we might want to go completely off grid. In order to afford to do that, we tried to design specifically to minimize electricity usage. This entailed other changes, on top of the above.

First, domestic hot water makes up 14% of household electricity usage. We draw hot water off the wood stove in the coldest months, which uses minimal electricity just to run an efficient pump. We shower out in the garden in the warmest months with solar-heated water. In the shoulder seasons when the wood stove isn’t running much but it’s too chilly to shower outside, we use an electric water heater that actually stays off most of the time. We turn it on for about 15 minutes, then off again before getting in the shower. This saves about 30% over leaving it on all the time. Altogether, those changes are worth over 3 kWh/day.

The wood stove does our winter heating and cooking as well, and it probably causes more pollution than using electricity for the same tasks (see an in-depth discussion here). Although we always consider environmental impact, for the crucial task of winter cooking and heating we decided based on resilience. When it’s hot I have a summer kitchen with a camp stove that uses about four gallons of gasoline a year, plus a solar oven and a solar dehydrator. All of these things must be done outside which keeps the heat out of the house, reducing the electricity needed for cooling.

Our house is banked into the ground (also called “earth-sheltered”). During the design phase, I hoped this would keep us from needing supplemental cooling, and it does, sort of. The temperature would be survivable, but to keep the humidity healthy we run the littlest window AC unit on the market, two to five hours a day.

In the hot months, therefore, our energy usage gets up to 5.2 kWh/day, whereas in the coldest months it’s down around 2.3 (winter is when other households in our area use the most, and that extra is typically met by the dirtiest fuels because those are the most flexible, so winter savings are especially environmentally friendly). We might use about 2.5 kWh/day for cooling on the days we need it, which is higher than I hoped but still pretty low.

Banking into the ground probably helps with heating, as well. The temperature at five feet below ground in our area is about 60 degrees, which is significantly warmer than the winter air temperature. When we go away for a week in December the house doesn’t fall below 54 degrees, even with no supplemental heat. The building is oriented east to west in accordance with good passive solar design, and there are lots of south-facing windows. This results in five degrees of temperature gain on even the coldest winter days, if the weather is sunny.

Obviously, nothing can be done about the orientation and earth sheltering of existing houses. If you’re thinking of building or buying a different house, though, it’s definitely worth it to choose with these things in mind.

Another change we made was getting rid of our refrigerator. These only use about 4% of household energy, but I also wanted a chest freezer to preserve garden produce and homegrown meat. I didn’t want to buy, pay to run, and make room for both fridge and freezer in my 725-square-foot house. I was captivated by Sharon Astyk’s unplugged fridge, which she described in Depletion and Abundance (in case you can’t get it through your library, that’s an affiliate link. My commission doesn’t raise your price, and it supports this site first, and then The Cool Effect). She kept the milk cool by swapping some bottles of ice over from her chest freezer. She had more kids and more goats than me; if she could do it, so could I.

I reasoned that a drawer-type organization might work better than a forward-facing door, which is notorious for wasting cold air by spilling it all over the floor. I designed an insulated pair of drawers that fit under the kitchen counter. Twice a day we pull two repurposed juice bottles of ice out of the freezer and pop them in the drawer. There’s a Tupperware pan to catch the condensation that forms on the ice bottles, which must be dumped in the sink. As long as I don’t overload the freezer and make it a pain to get the new bottles out, this is a 30-second procedure, just part of opening the kitchen in the morning and closing it in the evening.

How well does it work? Pretty darn well. Unlike a camp or picnic cooler, there’s no loose ice melting, so there isn’t a bunch of water floating everything. Milk and other very fragile foods go in the pan against the ice. Pickles, condiments and ferments like yogurt go next to the pan, where it’s a degree or two warmer. Apples, potatoes and other produce go in the bottom drawer, where the temperature is perfect for them. Leftovers cool on the counter and then go in the freezer, which is a safer procedure than putting them in the fridge anyway. We’ve forgotten to swap the ice maybe three times in over two years, but disaster did not ensue.

About the only thing that doesn’t keep at least as well as in a regular refrigerator is broccoli. I’m not sure why, but it goes brown a few days sooner. No matter. If I buy it from the store we eat it within 48 hours. Someday I’ll grow it successfully and eat it cut directly from the plant, only in season, plate after plate until I’m so sick of it I don’t even want to hear the word broccoli until next spring. It’ll be lovely.

My house has a lot of comfort built into it. We still have a lot of electrical devices, by global standards. I have a beloved crockpot, an electric kettle, a toaster oven and a food processor for making peanut butter and pesto. One or three of these devices is used every day. The kids watch four or six hours of something per week and the adults watch a similar amount. Our infant who never slept has grown into a boy who sleeps great, so we do much less middle-of-the-night screen time than we used to.

We also have a freezer, clothes washer, water heater and the pump that draws hot water off the woodstove. We have two laptops (which use about 1/5 the energy of a desktop), two phones, two drills and two saws, toys that run on rechargeable batteries, a vacuum, four ceiling fans, 18 LED bulbs. This time of year, there is a strand of festive lights on our live orange tree, which blooms at Christmas and makes the whole house smell like orange blossom.

All that adds up to a very modern life, not a primitive one at all. We’re very comfy, day to day, and we’re able to do everything we need to plus nearly all the things we want to in our lives. In terms of the history of humanity, this constitutes a fantastic amount of luxury, all for just 4.7 kWh/day.

Don’t worry for a moment if you can’t or don’t want to change all of these things. Changing a few or even just one is better than changing none, for the planet, for the pocketbook and for living a nicer life. Even a small reduction by a small fraction of people would wipe out America’s 0.2% annual growth in electricity consumption, sending us in the right direction. I’m not suggesting anybody upend their life. I invite everyone to join us on the surprising and fascinating journey of living just as well or better on less.

Written by Kara Stiff and originally published on Low-Carbon Life

About the Author

I have a BS in Sustainable Agriculture from the University of Maine, and I worked on sustainability issues in Native Alaskan communities through Cooperative Extension before moving to North Carolina. My goal with my writing and in my life is to inspire others to think critically about their choices in order to build communities that are happier, healthier and gentler on the planet.

You may also like

Making Your Home More Sustainable: Our Top Tips

The Most Effective Steps That Help You Become More Environmentally-Friendly

Sustainable Living 101: Here Are the Changes That Can Make a Huge Difference

How to Cool Down Your Home without AC